After the close of the war, Marvin continued to live in Medina, Lenawee County, Michigan from 1864 to 1868, then apparently he and his brother Dennis migrated west by way of Cape Horn and settled Santa Clara County, California 1 for a short time, then continued on to Oregon.

After the close of the war, Marvin continued to live in Medina, Lenawee County, Michigan from 1864 to 1868, then apparently he and his brother Dennis migrated west by way of Cape Horn and settled Santa Clara County, California 1 for a short time, then continued on to Oregon.

In 1869, Marvin filed a homestead claim and built a small cabin on land just out of Eagle Point, Oregon. That year, two tragedies occurred, Dennis died, and the cabin burned on Oct. 16, 1869. With determination and perseverance, Marvin built a large house strong enough to last a lifetime. The wood for the house was cut from trees above Prospect, Oregon

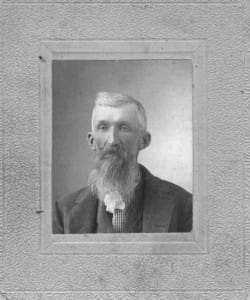

In early 1876, Marvin met Susan Carolina Griffeth, a local girl. They married on May 21, 1876 by the JP in Eagle Point, Oregon at the home of the bride’s father, Charles Griffeth. Marvin and Susan reared three children at the homestead, they were Ora, Mayme (Mamie), and Walter Wood.

The 1880 U.S. Census by Little Butte, Jackson, Oregon listed Marvin S. Woods age 43, Race W, Birthplace NY, Occupation as Farmer, and Father & Mother birthplaces as NY. Married to Susan C., age 24, with children of Ora (age 3) and Maimey (age 1). Included in the household was George Doney, Male, Race W, Age 26, Birthplace California, Occupation as Horse Breaker, Fathers birthplace Ohio, and Mothers birthplace Indiana.

After Susan and Marvin reared their three children at the homestead, Marvin separated from Susan in 1898 and he moved into Eagle Point. Susan’s divorce from Marvin was apparently final in 1900. In the 1900 U.S. Census, Marvin was listed as a widower, living in Eagle Point with his daughter, Ora Henderson, her husband Thomas and their daughter Veta, age 10 months.

Marvin, over the years, had suffered from his gun shot wounds he received in the Civil War. He had applied and re-applied for pension increases, and he was examined and re-examined by doctors over the years to justify his pension increases. His left arm became so disabled that he could do very little manual labor, besides his left jaw and face being badly disfigured from his wounds. . 2

Sometime after 1913, Marvin married again, to a widow by the name of Rachel (Gilpin) Wolary. She had been previously married to Nathaniel Wolary, also a Civil War veteran, who died Jan. 29, 1913 in Eagle Point. According to the 1920 Census, Rachel was listed as the spouse to Marvin.

Rachel Wood died Feb. 2, 1924 at the home of Dick Johnson, in Eagle Point, OR. She is buried at the Central Point Cemetery. Marvin died nearly a month and a half after Rachel, on March 16, 1924 at 3:30 a.m. Marvin had suffered his last years from senility, and eventually died from Prostatitis and Cystitis during his last month of life. He died in his son’s home, the one he had built several years before. According to his death certificate, Marvin’s mother was Elizabeth Cawson (Clawson), and father was Sylvester Wood. Marvin is buried at the Central Point Cemetery.

Rachel Wood died Feb. 2, 1924 at the home of Dick Johnson, in Eagle Point, OR. She is buried at the Central Point Cemetery. Marvin died nearly a month and a half after Rachel, on March 16, 1924 at 3:30 a.m. Marvin had suffered his last years from senility, and eventually died from Prostatitis and Cystitis during his last month of life. He died in his son’s home, the one he had built several years before. According to his death certificate, Marvin’s mother was Elizabeth Cawson (Clawson), and father was Sylvester Wood. Marvin is buried at the Central Point Cemetery.

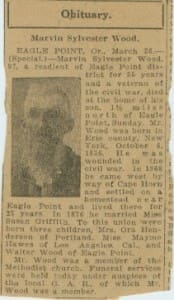

Obituary for Marvin S. Wood:

“Marvin Sylvester Wood 87 resident of Eagle Point for 55 years, Veteran of Civil War and was wounded, died Sunday (Mar. 16, 1924) at is son’s home. Mr. Wood was born in Erie Co. New York on 10-8-1836 and came west in 1868. Married Miss Susan Griffith 1876. Survivors are Ora, Mayme Hawes and Walter Wood. He was a Methodist and member of the G. A. R.” (Grand Army of the Republic). 3